Ulcerative colitis is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease that pursues a protracted relapsing and remitting course, usually extending over years. Ulcerative colitis involves the colon. The incidence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) varies widely between populations. There was a dramatic increase in the incidence of ulcerative colitis in the western world, starting in the second half of the last century and coinciding with the introduction of a more ‘hygienic’ environment with the advent of domestic refrigeration and the widespread use of antibiotics. The developing world has seen similar patterns, as these countries adopt an increasingly Westernised lifestyle. In the West, the incidence of ulcerative colitis is stable at 10–20 per 100 000, with a prevalence of 100–200 per 100 000. This commonly starts in the second and third decades of life, with a second smaller incidence peak in the seventh decade. Life expectancy in patients with IBD is similar to that of the general population. Although many patients require surgery and admission to hospital for other reasons, with substantial associated morbidity, the majority have an excellent work record and pursue a normal life.1

Ulcerative colitis is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease that pursues a protracted relapsing and remitting course, usually extending over years. Ulcerative colitis involves the colon. The incidence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) varies widely between populations. There was a dramatic increase in the incidence of ulcerative colitis in the western world, starting in the second half of the last century and coinciding with the introduction of a more ‘hygienic’ environment with the advent of domestic refrigeration and the widespread use of antibiotics. The developing world has seen similar patterns, as these countries adopt an increasingly Westernised lifestyle. In the West, the incidence of ulcerative colitis is stable at 10–20 per 100 000, with a prevalence of 100–200 per 100 000. This commonly starts in the second and third decades of life, with a second smaller incidence peak in the seventh decade. Life expectancy in patients with IBD is similar to that of the general population. Although many patients require surgery and admission to hospital for other reasons, with substantial associated morbidity, the majority have an excellent work record and pursue a normal life.1

Clinical features

- The cardinal symptoms are rectal bleeding with passage of mucus and bloody diarrhoea.

- The presentation varies, depending on the site and severity of the disease, as well as the presence of extra-intestinal manifestations. The first attack is usually the most severe and is followed by relapses and remissions.

- Triggering factors: Emotional stress, intercurrent infection, gastroenteritis, antibiotics or NSAID therapy may all provoke a relapse.

- Proctitis causes rectal bleeding and mucus discharge, accompanied by tenesmus. Some patients pass frequent, small-volume fluid stools, while others pass pellety stools due to constipation upstream of the inflamed rectum.

- Left-sided and extensive colitis causes bloody diarrhoea with mucus, often with abdominal cramps. Constitutional symptoms do not occur. In severe cases, anorexia, malaise, weight loss and abdominal pain occur and the patient is toxic, with fever, tachycardia and signs of peritoneal inflammation.1

Diagnosis

The most important issue is to distinguish the first attack of acute colitis from infection. A history of foreign travel, antibiotic exposure (Clostridium difficile/pseudomembranous colitis) or homosexual contact increases the possibility of infection, which should be excluded by the appropriate investigations.1

Complications

- Life-threatening colonic inflammation

This occurs in ulcerative colitis. In the most extreme cases, the colon dilates (toxic mega colon) and bacterial toxins pass freely across the diseased mucosa into the portal and then systemic circulation. This complication arises most commonly during the first attack of colitis and is recognised by the features. An abdominal X-ray is recommended to be taken daily in such cases because, when the transverse colon is dilated to more than 6 cm, there is a high risk of colonicperforation, although this complication can also occur in the absence of toxic mega colon. Severe colonic inflammation with toxic dilatation is a surgical emergency and most often requires colectomy.1

- Haemorrhage

Haemorrhage due to erosion of a major artery is rare.1

- Cancer

The risk of dysplasia and cancer increases with the duration and extent of uncontrolled colonic inflammation. Thus patients who have long-standing, extensive colitis are at highest risk. The cumulative risk for dysplasia in ulcerative colitis may be as high as 20% after 30 years. The risk is particularly high in patients who have concomitant primary sclerosing cholangitis for unknown reasons. Tumours develop in areas of dysplasia and may be multiple. Patients with long-standing colitis are therefore entered into surveillance programmes beginning 10 years after diagnosis. Targeted biopsies of areas that show abnormalities on staining with indigo carmine or methylene blue increase the chance of detecting dysplasia and this technique (termed pan colonic chromo-endoscopy) has replaced colonoscopy with random biopsies taken every 10 cmin screening for malignancy. The procedure allows patients to be stratified into high, medium or low-risk groups to determine the interval between surveillance procedures. Family history of colon cancer is also an important factor to consider. If high-grade dysplasia is found, panproctocolectomy is usually recommended because of the high risk of colon cancer.1

Extra-intestinal complications

Extra-intestinal complications are common in IBD and may dominate the clinical picture. Some of these occur during relapse of intestinal disease; others appear to be unrelated to intestinal disease activity.1

Investigations

- Investigations are necessary to confirm the diagnosis, define disease distribution and activity, and identify complications.

- Full blood count may show anaemia resulting from bleeding or mal absorption of iron, folic acid or vitamin B12. Platelet count can also be high as a marker of chronic inflammation.

- Serum albumin concentration falls as a consequence of protein-losing enteropathy, inflammatory disease or poor nutrition.

- ESR and CRP are elevated in exacerbations and in response to abscess formation.

- Faecal calprotectin has a high sensitivity for detecting gastrointestinal inflammation and may be elevated, even when the CRP is normal. It is particularly useful for distinguishing inflammatory bowel disease from irritable bowel syndrome at diagnosis, and for subsequent monitoring of disease activity.1

- Bacteriology

At initial presentation, stool microscopy, culture and examination for Clostridium difficile toxin or for ova and cysts, blood cultures and serological tests should be performed. These investigations should be repeated in established disease to exclude super imposed enteric infection in patients who present with exacerbations of IBD. During acute flares necessitating hospital admission, three separate stool samples should be sent for bacteriology to maximise sensitivity.1

- Endoscopy

Patients who present with diarrhoea plus raised inflammatory markers or alarm features, such as weight loss, rectal bleeding and anaemia, should undergo ileocolonoscopy. Flexible sigmoidoscopy is occasionally performed to make a diagnosis, especially during acute severe presentations when ileocolonoscopy may confer an unacceptable risk; ileocolonoscopy should still be performed at a later date, however, in order to evaluate disease extent. In ulcerative colitis, there is loss of vascular pattern, granularity, friability and contact bleeding, with or without ulceration. In established disease, colonoscopy may show active inflammation with pseudopolyps or a complicating carcinoma. Biopsies should be taken from each anatomical segment (terminal ileum, right colon, transverse colon, left colon and rectum) to confirm the diagnosis and define disease extent, and also to seek dysplasia in patients with long-standing colitis guided by pancolonic chromoendoscopy.1

- Radiology

Barium enema is a less sensitive investigation than colonoscopy in patients with colitis and, where colonoscopy is incomplete, a CT colon gram is preferred.1

Management

Ulcerative colitis is a life-long condition and has important psychosocial implications; specialist nurses, counsellors and patient support groups have key roles in education, reassurance and coping.1

The key aims of medical therapy are to: 1

- Treat acute attacks (induce remission)

- Prevent relapses (maintain remission)

- Prevent bowel damage

- Detect dysplasia and prevent carcinoma

- Select appropriate patients for surgery

Some complications

- Active proctitis

- Active left-sided or extensive ulcerative colitis

- Severe ulcerative colitis1

Patients who fail to respond to maximal oral therapy and those who present with acute severe colitis are best managed in hospital and should be monitored jointly by a physician and surgeon:

- Clinically: for the presence of abdominal pain, temperature, pulse rate, stool blood and frequency

- By laboratory testing: haemoglobin, white cell count, albumin, electrolytes, ESR and CRP, stool culture

- Radio logically: for colonic dilatation on plain abdominal X-rays.

Indications for surgery in ulcerative colitis1

Impaired quality of life

- Loss of occupation or education

- Disruption of family life

- Failure of medical therapy

- Dependence on oral glucocorticoids

- Complications of drug therapy

- Fulminant colitis

- Disease complications unresponsive to medical therapy

- Arthritis

- Pyoderma gangrenosum

- Colon cancer or severe dysplasia

Scope of Homeopathy

Homoeopathy has well recognized role to play in treating and managing Ulcerative colitis.

UC progression can be arrested to a great extent by constitutional or totality based homeopathic medicine. For acute episodes of pain there are many acute remedies which can be used for control of pain and inflammation. Regular use of constitutional remedy brings the ESR, CRP and other parameter down. Right medicine can lead a patient to lead a pain free and normal life.

It’s advisable to consult a registered homeopathic practitioner and take advice for a right homeopathic remedy.

Homeopathic Medicines for Ulcerative Colitis2

Argentum Nitricum

Argentum Nitricum

Gnawing ulcerating pain; burning and constriction. Ineffectual effort at eructation. Colic, with much flatulent distention. Stitchy ulcerative pain on left side of stomach, below short ribs.

Arsenicum Album

Arsenicum Album

Gnawing, burning pains like coals of fire; relieved by heat. Liver and spleen enlarged and painful. Ascites and anasarca. Abdomen swollen and painful. Pain as from a wound in abdomen on coughing.

Rectum – Painful, spasmodic protrusion of rectum. Tenesmus. Burning pain and pressure in rectum and anus.

Carbo Vegetabilis

Carbo Vegetabilis

Abdomen Pain as from lifting a weight excessive discharge of fetid flatus. Cannot bear tight clothing around waist and abdomen. Ailments accompanying intestinal fistulae. Abdomen greatly distended; better, passing wind. Flatulent colic. Pain in liver.

Rectum and Stool – Flatus hot, moist, offensive. Itching, gnawing and burning in rectum. Acrid, corrosive moisture from rectum. Burning at anus, burning varices .Frequent, involuntary offensive stools, followed by burning. White haemorrhoids; excoriation of anus. Bluish, burning piles, pain after stool.

Kalium Carbonicum

Kalium Carbonicum

Stitches in region of liver. Old chronic liver troubles, with soreness. Jaundice and dropsy. Distention and coldness of abdomen. Pain from left hypochondrium through abdomen; must turn on right side before he can rise.

Rectum – Large, difficult stools, with stitching pain an hour before.

Mercurius Solubilis

Mercurius Solubilis

Stabbing pain, with chilliness. Boring pain in right groin. Flatulent distention, with pain.

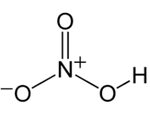

Nitricum Acidum

Nitricum Acidum

Great straining, but little passes, Rectum feels torn. Bowels constipated, with fissures in rectum. Tearing pains during stools. Violent cutting pains after stools, lasting for hours (Ratanh). Diarrhoea, slimy and offensive. After stools, irritable and exhausted. Colic relieved from tightening clothes.

Phosphorus

Phosphorus

Feels cold (Caps). Sharp, cutting pains. A very weak, empty, gone sensation felt in whole abdominal cavity. Pancreatic disease. Large, yellow spots on abdomen.

Pulsatilla Pratensis

Pulsatilla Pratensis

Painful, distended; loud rumbling. Pressure as from a stone. Colic, with chilliness in evening.

Diet recommendation for Ulcerative Colitis

Food to be taken

- Easily digestible food – like apple sauce

- Ripe bananas and canned fruits

- Cooked vegetables – like carrots and spinach

- Probiotics – Yogurt can provide with some protein and probiotics – if not lactose intolerant

- Salmon – has healthy omega-3 fatty acids that may help reduce inflammation.

- Nut butters – Peanut butter, almond butter, cashew butter, and other nut butters. Choose creamy peanut butter instead of chunky to avoid having to digest difficult nut.

- White rice with turmeric

Food to be avoided

Food to be avoided

- Alcohol

- Caffeine

- Carbonated drinks

- Dairy products, if lactose intolerant

- Dried beans, peas, and legumes

- Dried fruits

- Foods that have sulfur or sulfate

- Foods high in fiber

- Meat

- Nuts and crunchy nut butters

- Popcorn

- Products that have sugar-free gum and candies

- Raw fruits and vegetables

- Refined sugar

- Seeds

- Spicy foods

References

- Ralston S.H., Penman I.D., Strachan M.W.J., Hobson R.P. Davidson’s, Principles and Practice of Medicine. 23rd rev.ed. Edinburgh; Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2018. 1417p.

- Boericke W. Pocket Manual of Homoeopathic Materia Medica. New Delhi: B. Jain Publishers (P) Ltd.; 2011.